By David Sibley

(From SHIPPING Today and Yesterday)

IN SEPTEMBER, 1947, a British Military Court war crimes trial was held in Hong Kong in to the execution of crew members and passengers of the British cargo ship Behar, 7,840grt, owned by the Hain Steamship Co., a subsidiary of the P. & 0.Steam Navigation Co. The Behar had been sunk on Mar. 9, 1944, by the Japanese heavy cruiser Tone, under the command of Captain Mayazumi.

The cruiser was part of the Japanese 16th Squadron of the South West Area Fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral Sakonju, who flew his flag in the cruiser Aoba.

At the trial, Vice-Admiral Sakonju was charged with giving the order to execute the approximately 65 prisoners, and Captain Mayazumi was charged with carrying out that order. However, the owners stated to the court the official figure was 72.

The Japanese South West Area Fleet headquarters was located at Penang and at a conference held in February, 1944, it was decided that Allied shipping was to be attacked in the Indian Ocean with a view to disrupting the Allied supply routes.

The order was given that wherever possible. Allied ships should be captured and not sunk. The order also stated that if it became necessary to sink ships, only the minimum number of prisoners thought necessary for interrogation were to be taken on board the Japanese warships and brought back to base. The Japanese hoped to learn something about Allied shipping movements from the prisoners.

On Feb. 27, the 16th Squadron task force consisting of the three heavy cruisers Aoba, Tone and Chikuma, under the command of Vice-Admiral Sakonju, sailed from Singapore and the following day the ships left the Banka Strait and then headed through the Sunda Strait and in to the Indian Ocean.

The task force headed for an area south-west of the Cocos Islands where it searched for Allied shipping sailing between Australia and India, but after a short time in this area without success, the Japanese ships turned northwards. On Mar. 9, the Tone sighted a ship which turned out to be the Behar.

The twin-screw motor-ship Behar had only been completed by Barclay Curle & Co., on the Clyde, in August, 1943; the ship, which had a speed of 16.5 knots, was not of a standard war-built design but had been built under special licence to her owner’s accommodation for 12 passengers. The Behar was more heavily armed than most cargo ships in wartime, having one 4-inch and one 3-inch dual-purpose guns, a multiple rocket launcher, 20mm. Oerlikons. , and a .5- inch Browning machine gun. In addition, and most unusual for a merchant ship, she was fitted with Asdic and carried depth charges.

The ship had a complement of 102, comprising 18 British officers, 67 Indian ratings, 15 Royal Artillery Maritime Regiment/DEMS gunners, and two Asdic operators. The Master was 51-year-old Captain Maurice Symonds, born in the West Country but living in Glasgow; the Chief Engineer, James Weir, aged 58, of Glasgow, had along with the seven Scottish engineers stood by the ship whilst being built. The Chief Officer was William Phillips, of Cardiff, and she also carried 2nd, 3rd, and 4th officers and two apprentices. The radio department consisted of three Radio Officers, Arthur Walker being the First Radio Officer. The gunners were led by Petty Officer W. L. Griffiths.

The Behar sailed from Melbourne on Feb. 19, bound for Bombay and carrying only a cargo of 796 tons of zinc, her ultimate destination being the U.K.

She also carried nine passengers, comprising Captain P. J. Green, of the Indo-China Steam Nav. Co.; three Royal New Zealand Navy officers; a Royal Air Force Flight Sergeant; two female passengers; Dr. Lai Young Li, a Chinese physician; and Duncan MacGregor, a retired Australian bank manager.

On the morning of Mar. 9, the weather was quite hazy, with visibility less than two miles. Suddenly, out of the haze came the cruiser Tone, her guns already trained on the Behar. The signal lamp on the cruiser ordered the cargo ship to heave to.

Capt. Symonds ordered the radio officer on watch to send the ‘RRR’ signal (‘I am being attacked by a raider’). As the signal started to be transmitted, the cruiser opened fire. At such short range, it was devastating.

Such was the ferocity of the Japanese attack that the gunners on the Behar were unable to fire a single shot before the order was given to abandon ship as the Behar was soon ablaze and sinking. Two of the DEMS crew and a rating died in this attack. In all 108 people managed to get away in the four lifeboats, an amazing feat under such terrible bombardment. The ship is recorded as sinking south-west of the Cocos Islands at 20.32S 87.10E.

Shortly after the Behar had been abandoned, the Tone hove-to near the lifeboats and, under threat of machine gunning, ordered all the survivors on board the cruiser.

Once on board, the survivors were relieved of most of their clothing, their arms were tied behind the back, and they were forced upwards by a rope tied around their necks.

The two women were not excluded from this ordeal.

Chief Officer Phillips, a heavily-built robust man, vehemently protested at this violation of the Geneva Convention and was rewarded with a savage beating with a baseball bat. On his knees and bleeding, he continued to protest until the arrival of a senior officer who released the women.

The prisoners were then made to sit on deck in the hot sun for several hours, bound up, before being taken down below. Here, they were beaten, and kept in a badly-ventilated and poorly-lit compartment for six days. They were just let up on deck for brief spells.

Meanwhile, Capt. Mayazumi had informed Vice-Admiral Sakonju of his success in sinking the Behar and that he had 108 prisoners. Sakonju was annoyed that the Behar was not captured as stated in his orders and was furious that so many survivors had been taken on board. He re-minded Mayazumi to follow orders of keeping only a few survivors.

Capt. Mayazumi asked what he was to do with the ‘other’ survivors? Back came the reply: “Dispose of them.” Capt. Mayazumi disagreed with this order as did Commander Mil, of the Tone, with whom Mayazumi had consulted. Mayazumi then requested that he be allowed to land all his prisoners at Tandjong Priok, the port for the capital city of Batavia in Java. The order came back: “Dispose of the prisoners immediately.”

Capt. Mayazumi had still not carried out this order when the three cruisers arrived off Tandjong Priok on Mar. 15. Capt.Mayazumi went to visit the Vice-Admiral and begged him to spare the lives of the prisoners. Sakonju’s wrath was such that Mayazumi’s previous defiance of the order evaporated. Mayazumi returned to his ship and informed Cmdr. Mii that it was hopeless – the order must be carried out when the ship sailed. Capt. Mayazumi was unusual for a Japanese, in that he was of the Christian faith, while Cmdr. Mii was not a Christian but he shared his Captain’s view of human life in not wanting to kill innocent prisoners.

Later that same morning, the obscene selection of those who would live and those who would die took place on the Tone. The following were selected to live, in captivity: Capt.Symonds, Chief Officer Phillips, Chief Engineer Weir, Radio Officer Walker, Petty Officer Griffiths, 21 English-speaking Indian ratings, the two Asdic operators, and seven of the nine passengers, including Doctor Lai Young Li and the two women—a total of 36.

Those who were to live were transferred to the cruiser Aoba and were later landed at Tandjong Priok. Those who remained on the Tone probably had no idea of the fate awaiting them and may have thought that the selection of senior officers from the Behar was an indication that they were being taken away for special interrogation.

The Tone sailed on Mar. 18, and that evening, Capt, Mayazumi ordered Cmdr. Mii to execute the prisoners. The Commander refused to carry out this order. Capt. Mayazumi then instructed a Lieutenant (Ishihara to carry out the order. That night, Ishihara, Lieutenant Tani, Sub-Lieutenants Tanaka and Otsuka, plus several other officers, lined the prisoners up on deck. Each prisoner was felled by a blow to the stomach and kicked in the testicles before he was beheaded. Meanwhile, the prisoners who had been taken ashore were kept in a small room in the local office of the Dutch shipping company Royal Interocean Lines for two days. Then the Chief Officer, Chief Engineer, the two Asdic operators, Petty Officer Griffiths, Dr. Lai Young Li, and six or seven ratings were moved to a prisoner-of-war camp outside Batavia.

Capt. Symonds, Capt. Green and Radio Officer Walker were thus separated from the others and never saw them again in Java. The two women were taken to a women’s camp. The survivors who had been taken to the camp outside Batavia were kept in isolation from prisoners in the rest of the camp for many months, suffering privation, beatings and interrogation in various buildings in Batavia.

Chief Officer PhiIIips, who had already been badly beaten on the Tone for protesting about their treatment, was placed in solitary confinement. Bound hand and foot, with a bamboo lashed across his throat to prevent sleep, and thrown into a small wooden hut not much larger than a dog kennel, Mr PhiIIips kept his sanity, as the days went by, by forcing himself to do intricate feats of mental arithmetic and studying a young plant seen growing through a tiny window. Eventually, the Japanese accepted that nothing of value could be learned from the men of the Behar and they were moved in to the main camp, which held British, Australian, American and Dutch servicemen and civilians.

Unknown to the other survivors, Capt. Symonds, Capt.Green, and Radio Officer Walker were sent to Japan to work in the mines. For 15 months, the survivors endured a starvation diet and ill treatment, and as Japan’s situation in the war worsened, so did the treatment suffered by the prisoners, who feared what the Japanese might do to the the face. But liberation finally came. Chief Officer Philiips reached home in October, 1945, and one of his first sad duties was to call on the wife of Second Officer Gordon Rowlandson and the mother of Apprentice Denys Matthews, both fellow Welshmen, with a few words of comfort.

At the military trials in Hong Kong of Vice-Admiral Sakonju and Capt. Mayazumi, Commander Mii gave the following evidence:”On the evening of Mar. 18, I was told by Captain Mayazumi that the execution of the prisoners still remaining onboard must be carried out that night at sea. I refused to be associated with the execution, so the captain issued orders direct to Lieutenant Ishihara.”I cannot now remember the names of the members ofthe execution party, but learnt that most of them were gunroom officers, although Lieutenant Tani and few other wardroom officers were in the party. I later heard Sub-Lieutenants Tanaka and Otsuka boasting of their participation of the execution. As I was not an eyewitness, I could not describe the exact method used.”

The owners of the Behar supplied the following information to the court:

On board: 44 Europeans, 87 Indians

Saved: 15 Europeans, 17 Indians

Killed in enemy action: two Europeans, one Indian Died in internment: four Indians Murdered by Japanese on or about Mar. 19, 1944: 27 Europeans, 45 Indians.

The court convicted Vice-Admiral Sakonju and sentenced him to death, but showed sympathy for Capt.Mayazumi and sentenced him to seven years in prison.

Authors Note:

I am greatly indebted to Captain Bernard Edwards for allowing me to use material he researched for his book ‘Blood & Bushido’ and to quote widely from the book. There is so little published about the loss of the Behar and the atrocities carried out to the crew and passengers that one could take the view that it has been swept under the carpet, along with other atrocities committed at sea by the Japanese to Allied merchant seamen.

Capt. Edwards is to be thanked for drawing attention to this dreadful episode of the war at sea. The Hong Kong Military Court evidence given by Commander Mii can be found in Lord Russell’s book ‘Knights of Bushido’ which I have quoted from. Also it should be noted that the spelling of the Japanese captain’s name is given as ”Mayazumi” The other point of difference In Lord Russell’s book is the statement that 32 survivors were landed in Java, 15 Euro- pean and 17 Indians. Could it be that Captain Edwards is correct in stating that 21 Indians went into captivity and that the four dying in captivity would make the correct figure of 17 saved as per the owners’ statement to the court?

The General Register of Shipping and Seamen in Cardiff lists in their records, taken from the ship’s articles, that there were 63 Indian ratings, of whom 17 survived, one was killed by enemy action, 42 died on or about Mar. 18,1944, whilst prisoners of war, and three dying in imprisonment during 1944.

There is certainly conflict with the numbers given to the Hong Kong court by the ship’s owners.

With regard to the passengers, the G.R.S.S. records show only one female passenger being on board, but lists another passenger Mr G. Pascheove. However, in a written statement, Petty Officer Griffiths clearly states that there were two lady passengers and he visited them in their camp when the war ended.

The location of the Military Court papers is a mystery. Are they still in Hong Kong? These are now trying to be traced to find the charge sheet. In the book ‘Blood & Bushido’, the 2nd Engineer is reported to have been taken into captivity. However, in the register from whtoh the Merchant Navy Memorial names are taken, the date that Mr Edward McGinnes died is recorded as being on Mar. 18-19,1944, which is the date of the mass execution on board the Tone.

Yet another mystery remains, the identity of the second passenger murdered by the Japanese. Mr Duncan Macgregor is reported to be one of the two passengers executed.

However, If 15 Europeans were landed, four being the Behar officers, the Petty Officer gunner, the two Asdte operators, then the remaining eight must have been passengers, and only one could have been murdered. It is known that CapL Symonos, Capt. Green, Mr Phlllips, Petty Officer Griffiths and the two lady passengers survived captivity.

The Hain Steam Ship Co. ceased to exist in the early 1970s. Does anyone know what happened to the company’s records?

I am grateful to Mr S Cook, curator of the St Ives museum and to Mr George Monk for their help. My thanks to Mr P Dunbavand for giving me my first sighting of Capt. Edward’s excellent book, which gives a very detailed account of the Behar and other harrowing stories of atrocities committed by the Japanese at sea during the Second World War.

If any person can help fill in missing names, or has newspaper cuttings concerning survivors or the Military Court trial, I would very much like to hear from them.

My aim is to fill in the missing names, so that in the case of the Behar, for the first time, names of those who died, then it can be stated: “No one is forgotten, nothing is forgotten”

DAVID SIBLEY

Webmasters note:

I am indebted to Shipping Today and Yesterday for permission to reproduce this article and of course to the author David Sibley. Thanks also to TASC Member George Wade for highlighting this account of the fate of the Behar. I certainly was not aware of it, and I imagine this atrocity which took place 65 years ago is not widely known.

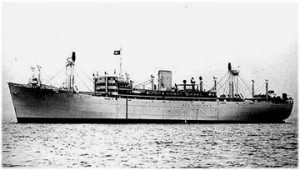

The Hain Steamship Co. Cargo ship ‘Behar’ 7849 grt built by Barclay Curle & Co. On the Clyde in August 1943 and sunk by Japanese cruiser ‘Tone’ March 1944

The Hain Steamship Co. Cargo ship ‘Behar’ 7849 grt built by Barclay Curle & Co. On the Clyde in August 1943 and sunk by Japanese cruiser ‘Tone’ March 1944

It is my understanding from my father that his brother Neil Brodie was a gunner executed in the incident. Neil was from Cambeltown in Scotland.

I have my late fathers book on the massacre,which my father told me about when he was alive.He was good friends with Denys Matthews(apprentice) who was executed on the ship.Denys and my father lived in the same street in Rumney,funnily I live in my fathers boyhood house now and Denys’ sister in law lives in Denys’ boyhood house.Denys’ brother lives 2 streets away.Although I’m too young born 1965 to have known Denys I have a picture of him in uniform with my Dad.My mother who is 85years said he was a great dancer.I just find the whole thing very sad and cant begin to imagine what his parents went through.

My uncle was a gunner on the Behar. Gnr Street.

My mother has his medals and paperwork advising of his death on the 18/19 March. He was one of those captured then slaughtered.

She is donating all this paperwork and medals to the Burma Star Benevolent Fund for their proposed museum.