Old Glox’ Ghost

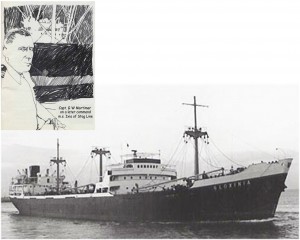

By Capt. GW Mortimer

(The Compass Magazine Sept/Oct 1969)

Submitted by TASC Member George Wade

‘So you’re not superstitious – you don’t believe in ghosts’

Neither did the master of the Steamship Gloxinia.

Until I served in the old Gloxinia I was strongly opposed to any opinions that supported beliefs in ghosts and supernatural apparitions, spirits, and the restless dead. When I left that ship, I had an open mind on the subject and now will listen with some sympathy to narratives of experience with unearthly forces. Sailors as a group tend toward easy acceptance of superstition and belief in the hyperphysical. It has been written that ignorant people in general tend to these beliefs naturally, the supposition being that the educated mind can provide reason and explanation for most occurrences within the bounds of live agency.

When I first took over command of the old tanker during the last war, I found great difficulty in settling into my position due to a variety of factors. She was an old, rather neglected ship, full of years and sores; verminous, stinking of fish oil, her crew was slack, and the senior officers were all much older than I. They rather resented my efforts to tighten up on efficiency. This entailed some rather blunt talking on my part and liberal use of the prod toward getting the ship running as I wanted her. I was accustomed to smart ships and smart officers running them. My ideas were still not run down to the point where they found excuse in the fact there was a war on, so why bother about exerting ourselves—we might all be in Davy Jones’s locker tomorrow!

In early conversations with my officers, mainly devoted to searching for information and knowledge of her, I was asked whether I believed in the existence of ghosts. In my position as master I could not, in all prudence, contribute anything to such beliefs, since I considered any convictions of this kind were apt to be a liability on board. Having ghosts in any ship’s company always imposed a certain strain on the crew and officers. To the question, therefore, I gave an emphatic negative, adding that such fantasies were only the products of rather weak intellects and the imaginative minds of those who did not give sufficient concentration to the business on hand. I had better things to think about than such childishness!

This ill-natured reply was not well received, and I was told that if I stayed very long in that old ship, I would have reason to change my mind. Lightly I asked what particular form the spooks haunting the ship took. Were we bothered by groans and clanking chains? Were the decks populated by ghouls sorting heads in the scuppers? Did they promenade at night keeping the ship awake? This rather goaded the older officers and they began relating incidents of seeing, hearing, and acting upon the advice of their favourite spectre, which had long sailed in that ship. Apparently he was an old man who had served many years in sail, and his son had once commanded the old ship in which we were serving. The old chap had taken a fancy to the Gloxinia, and he was still keeping a watching brief on us all and of her conduct and safety. They quoted cases wherein old Captain Leathers had appeared and given aid and warning of peril that when acted upon, proved the old boy knew what he was doing and was still a smart sailor, it not entirely an asset to have around. I listened to a great number of strange stories, with much scepticism, one in particular trying my credibility to such a point that I burst into loud guffaws.

Gloxinia had been at sea off the North-western Approaches; dusk was shading the sky, and the captain of the ship—the son of the ghost—was in his cabin. The officer of the watch was startled when the captain dashed onto the bridge shouting “Hard-a-port!” As the ship turned to her helm, a torpedo ran just clear of her stern. But for the timely alteration of course, she would have been clobbered. The mate, who was on watch, asked the captain how he had known that a torpedo was speeding towards them.

He replied that he had not known of the torpedo, but he had known that the ship was in danger because his father had appeared at his door and told him to get up on the bridge quickly and put the helm hard-to-port. I laughed heartily at this yarn as a rather humorous piece of fiction.

We sailed in due course and crept down river in a late October mist. After the tugs had been let go, I instructed the mate to swing out the lifeboats and grip them down in the emergency position, a normal wartime practice. He protested that they never swung the boats out at night-only during the daylight hours. Curtly I told him to carry out my orders, pointing out that the war did not cease at night, and that it would be good practice in any case for him and his men to know how to do the work in the dark. He went about the task, in the course of which a man fell from the boat deck to the main deck and received such injuries that I had to land him in the care of the Examination Vessel patrolling at the mouth of the river. After we had settled again on course, the mate came to me and said that Captain Leathers was now half right in that he had told him, when the mate had met the ghost on the foredeck as he was coming aft, that we would lose two men that voyage. I snorted in disbelief and told him to keep such silly rubbish to himself, for I did not want the crew to become jittery. At four o’clock the following morning, the visibility being good and the mate picking up the watch, I decided to go below and snatch a couple of hours of sleep. Coming down off the bridge, I paused on the lower bridge and took a look at my blacked-out ship. All was quiet. I could hear the dull thud of the old engines pushing the girl along; the bow waves hissed and sparkled in the night, and my mind was at rest. She felt good under my feet, and I was warming to her with a respect difficult to define, except to say that ships have a way with a sailor, and I knew that she and I would get along all right. Glancing out to the port side of the lower bridge, I noted a figure standing in the extreme wing looking out ahead. I walked across, and as I approached, I called out, “Who is that? What are you doing here?” There was no one there. Strange! I must have been tired. Staring for long hours into the night can make one’s eyes play tricks. It could not have been one of the watch, and the gunners were in the gun pits.

We steamed up the West Coast of Scotland that day and late that night. Conforming to orders, I took the ship into Loch Ewe and anchored her in the midst of other darkened ships. After Convoy Conference next morning, I came back on board, and all access to the shore was severed. Just before 3 P.M. we weighed anchor and began steaming slowly seaward preparatory to taking our place in a convoy bound for Iceland. At 4 P.M. the chief engineer reported that one of his firemen was missing and had last been seen just after 3:40 P.M. when he had called the four-to-eight watch. I cut speed to Dead Slow, handed her over to the mate, and went to investigate. A thorough search of the ship showed that the man was not with us. He could not have gone ashore since we were underway long before he was last seen. Then I noticed a pair of shoes near the rail on the poop. None of my crew claimed them, and they had not been there at 3 p.m. were they the missing man’s? Probably. He was a type, according to his mates, whose mind was morbidly fixed on the perils of life at sea in wartime. He brooded, and his only conversation was of what would happen if…. Most of us never let our minds dwell on such things. We were prepared to fight for survival, and we did so in every way we knew, but after that was done, our minds turned away from that aspect of our existence and we trusted in that special Providence which we firmly believed looks after fools, drunken men, and sailors.

I made a signal to the Examination Vessel on duty off the entrance to the Loch reporting the missing man. In my log book, I gave the opinion that the man, scared of seagoing in wartime, may have thought that the shore looked very near as we were leaving the Loch, and evidence suggested that he perhaps believed he could safely swim ashore. The water was very cold. It was only late that night as we were being hammered by a westerly gale that I remembered the mate’s words—we would lose two men on that voyage.

The day following the gale, it had just grown dark when the lookout man left his post on the forecastle head, came up to the bridge and reported to the mate that he was not going to keep the lookout forward in the bows. There was a man, or a ghost, moving around the forecastle head, and he was scared. I listened in on this report and questioned the man myself. Undoubtedly he was scared of something. The weather had moderated, and the ship was dry forward, and he seemed a sincere enough type. The mate listened quietly as I mocked at the man’s childishness and fears and told him that I would go forward with him and prove that there was no one there, but he flatly refused to accompany me. Clutching a flashlight, but careful to show no light as the convoy was blacked out; I went forward and climbed the ladder to the forecastle head. A diligent search revealed nothing untoward, and I came down the port side ladder and went under the forecastle head. With the aid of the flashlight I inspected every likely corner of concealment and even went down the forepeak store but found no evidence of human or ghostly presence. I stood for a few minutes outside of the starboard entrance to the forecastle letting my eyes adjust to full darkness. I had taken only a few steps when something impelled me to turn and look back. A man stood there looking out ahead! I presumed the mate had persuaded the lookout to return to his post, and intending to speak to him; I climbed the ladder, rounded the windlass—and found no one there.

The months that followed brought to me a succession of small incidents which I found increasingly difficult to explain to myself, yet I fought against giving credence to the idea that the ship was haunted.

On a voyage immediately after the closing of hostilities in Europe, we were bound up the Irish Sea with a new crew I had shipped at Liverpool, among whom was a new second mate. I considered myself lucky to have this officer, for he boasted a first mate’s certificate, and I thought he would be a man who knew his business. It was night as we held the ship on a course to clear Skerryvore, southwest of the island of Tiree and Barra Head on the southern tip of the Hebrides group. The helmsman was steering Nor-Nor-West, and at something after midnight, I decided that I could leave her to the second mate and take some rest. He appeared to understand my orders and advice on tide, and I left him with the injunction to call me at once if anything worried him or if he needed assistance.

Off the bridge, I cleaned up and was in my bunk before 1 A.M. listening to the fresh north wind and the rattle of spray on the bridge house. Following upon long established habit, I picked up a book and began to read myself to sleep. It was an interesting book, and tiredness seemed to have left me. My bunk light left just a circle of light about my head and pillow, and the rest of the cabin was almost dark. I started up on my elbow as my door was flung open, and a man stood there in the dim light, his oilskins gleaming wetness. He was, I thought, bearded, muffled up to his chin, a sou’wester pulled well down on his head. “Captain, you should get up on the bridge at once!” Annoyed by the man’s tone and his failure to knock at my door, I asked sharply, “Did the second mate send you down for me?” “No. But you get up on the bridge right away, or you are going to lose your ship!” He closed the door as I jumped out of my bunk, dug my feet into slippers, flung on my dressing gown, and dashed after him. I took the bridge ladder in three leaps, and my hair stood on end! There on the port bow with considerable elevation to it, was Oversay Light, which we were to have passed four miles distant on the starboard beam. I yelled for the second mate. He appeared, and I demanded to know where we were and how did he come to get that light on the port bow? All this took but seconds. Then I shouted, “Hard-a-port!” to the helmsman, at the same time running to the compass where I saw the ship was heading northeast—six points off her course. The second mate reckoned she was about a quarter of a mile off the rocks! “Stand by engines,” I ordered. The telegraphs rang, and I sweated cold fear as I watched that light slowly, oh so slowly, draw ahead, and then swing faster away onto the starboard bow. Breakers seemed to lick at her hungrily, and I held my breath waiting for the tearing of rock on metal under my feet. My mouth was parched, and my pyjamas were saturated with perspiration. She kept swinging to her helm, and I relaxed my grip on the dodger as the light drew astern and I steadied her on a course of southwest. Angrily I ordered the second mate to do nothing on the bridge until I gave him permission and went below to dress. Returning, I took time to cool off and check bearings and to resume our proper course, then demanded an explanation from the second mate how he came to be so far off course and heading for the rocks of Islay.

In the chartroom, he showed me his workmanship. The man had no idea what he was about. Every conceivable error it was possible to make, he had made. His chart work had showed him, in error that the ship was setting heavily to the eastward and he had begun to pour allowance for this set into the course, but he applied this allowance to the eastward. If, when driving your car, you see something to which you estimate you are going to pass too close, you do not turn towards it, but this is precisely what the second mate had done!

Next I asked to see the standby man of the watch and inquired if it had been he who had come to my cabin and told me to get up onto the bridge. He denied having done so and did not; in any case, fit my picture of the man who had stood at my door. The lookout man also denied having called me, but he thought he had seen someone coming along the deck about the time in question. I saw that watch out, and when the mate came up at 4 A.M., I told him of the incident and mentioned that I was going to find the chap who had sense and initiative enough to save the ship by calling me. The next morning I invaded the crew’s quarters and told the men that I owed much to one of them, and I wanted the man who had called me just after 2 A.M. that morning to step forward. There was no response, nor was there any member of the crew wearing a beard. Someone had certainly called me.

A dreadful feeling of doubt possessed me. Had I fallen asleep for an instant and dreamed the whole thing, or had some man in the ship’s company indeed called me but for reasons best known to himself decided to keep quiet about the matter. I considered these and many other explanations, but reached no satisfactory conclusions. I eventually left that ship after many years of service in her, with a wide open mind on the subject of the supernatural.